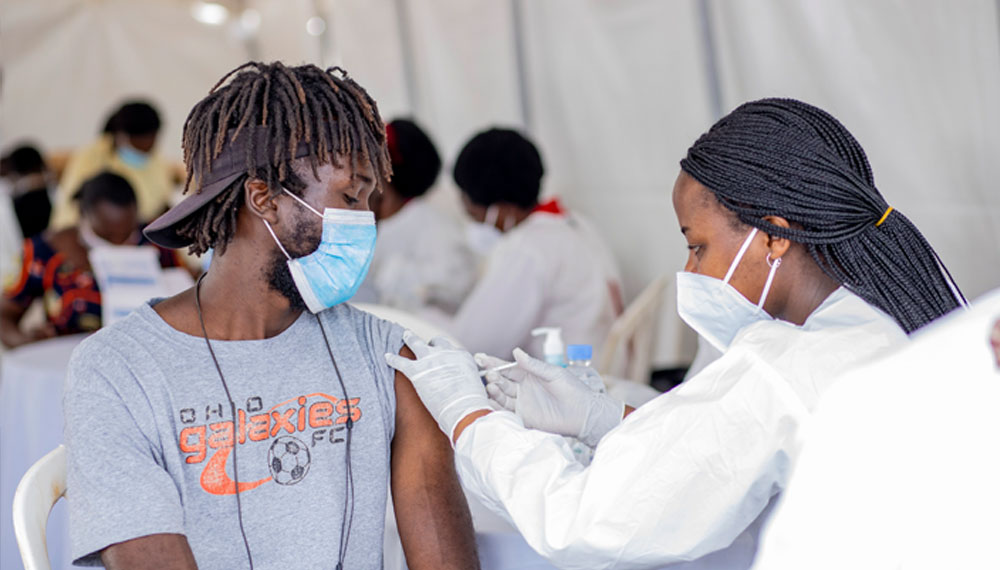

The World Health Organization (WHO) set a goal in October 2021 to fully immunise 70% of each nation’s population against COVID-19 by the end of June 2022. Many Covid-19 vaccination programmes in developing countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, were just getting started at the time, whereas many high-income countries had already achieved this objective. With a combined population of one billion, nations in the African Region (a WHO region that omits countries in north Africa, including Morocco and Egypt) had only received 200 million doses, which was the main obstacle impeding vaccination rates.

However, when vaccine supplies grew in the months that followed, the quantity of doses given did not. Only 25% of the dosages delivered to African nations were ready to be administered as of October 2021. Ten months later, that percentage has increased to 37%. Vaccination rates have now started to decline in several African nations despite greater vaccine accessibility. For instance, South Africa has used barely 14 doses per 100 people so far in 2022, compared to the 41 doses per 100 people it provided in the second half of 2021. Between March and May, 82 million doses were given in the African Region, down from 128 million over the previous 3 months.

In order to keep the pace of inoculation campaigns, it would have been simpler for African countries to acquire vaccines sooner, according to Vidya Sampath, director of the healthcare delivery NGO VillageReach’s Covid-19 vaccine delivery plan. By not having the vaccine prepared and accessible in 2021, the worldwide movement missed the window of opportunity to meet an increase in demand, especially in Africa. There is a plentiful supply right now in 2022, but people see risks far less seriously.

Covid-19 has spread over the continent in waves, but the effect on many people, especially the young Africans, has been minimal. According to the WHO, just 8% of the additional deaths caused by COVID-19 worldwide in 2020 and 2021 happened in Africa. In comparison, about 16% of the world’s population resides in Africa. According to Sampath, vaccine hesitancy has frequently been confused with Africa’s decreased demand for vaccines. Adam Bradshaw, a specialist in COVID-19 policy and advisor to the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, concurs that it’s more complicated than merely conspiracy ideas, but lower danger makes individuals more apathetic.

Governments now have the responsibility of directly distributing vaccines since citizens are less prepared to make time and financial sacrifices in order to receive vaccinations.

One strategy, according to Bradshaw, is for African nations to combine the COVID-19 vaccine with other lines of interaction with the healthcare system. According to Bradshaw, the goal of integrating health services is to maximise the scarce resources that are genuinely available. People are being urged to acquire a COVID-19 vaccine if they go to a clinic for their children’s vaccinations or for an adult medical evaluation.

Sampath claims that vaccination efforts in Ghana and the Democratic Republic of Congo have changed to put more of an emphasis on reaching vaccine-ambivalent people right where they’re standing. According to Bradshaw, numerous programmes have begun using mobile vaccination tactics, in which medical professionals visit villages to provide vaccines, in response to poor immunisation coverage in rural areas.

Sampath claims that one of the main obstacles preventing higher immunisation rates in Africa is a lack of professionals. According to data from the World Bank, before the pandemic, the number of doctors and nurses per 1,000 people in continental Africa ranged from 4.2 in Eswatini, then recognised as Swaziland, to just 0.2 in Chad. In contrast, there are 14 doctors and nurses for every 1,000 people in the European Union.

African nations also spend much less on healthcare than high-income ones. According to evaluations by the non-profit organisation CARE, the average “tarmac-to-arm” transportation price for a single dose of vaccine in South Sudan is $9.97, which is equal to 40% of the nation’s pre-pandemic per capita healthcare spending.

Sampath claims that the inability of African countries to redeploy people to work at mass vaccination sites, which were widespread in richer countries, is due to limited finance and a shortage of healthcare workers. For a four-to six-month endeavour, mass immunisation sites in just one city cost millions of dollars. African nations just do not have access to that kind of financing, said Sampath.

In response, Ghana established a National COVID Vaccination Day and adopted successful tactics from past immunisation programmes, such as those for polio. Ghana also carried out two mass immunisation campaigns, lasting one week each, during which time medical personnel briefly focused their attention on the COVID-19 immunisation effort before resuming their regular duties.

Their pre-pandemic healthcare readiness index, which ranks nations based on their health spending, the size of their medical workforce, and vaccination rates for other diseases like tuberculosis and hepatitis B, demonstrates how important the pre-existing public health system has been to vaccination advancement. The African Region nations with the least past investment in their healthcare systems have often struggled to build up immunisation programmes.

For instance, the five nations in the African Region with the highest vaccination rates spent, on average, over ten times as much per person on healthcare as the five nations with the lowest vaccination rates, and they hired six times as many doctors and nurses.

The ranking also identifies nations like Mozambique and Rwanda whose immunisation programmes have worked better than anticipated.

The vaccine deployment in Mozambique, according to Sampath, is a great success story. Mozambique first gave vaccinations in stages, starting with all medical personnel, then everyone over the age of 65, and then people over the age of 50 who had comorbid conditions. They managed their limited supply because they went looking for these very precise high-risk groups, according to Sampath. Unfortunately, many countries weren’t assisted in order to do this, which requires a lot of organisation and planning. Because of the effectiveness of Mozambique’s distribution method and the continuous promotion of vaccines by elected leaders, the programme gained the trust of the public, which supported continued demand.

Government officials in Rwanda have continuously emphasised the advantages of vaccines, similar to those in Mozambique. The Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA vaccine, which must be held at extremely low temperatures, was exclusively used in the capital, Kigali, where freezer equipment could be maintained. Rwanda was also lauded for its early preparation on which vaccinations to deploy in different places.

A glimpse of what may have been achievable in Africa if investments in vaccine development and distribution had been made is provided by the effective deployments in Mozambique and Rwanda. According to Sampath, the worldwide community took a chance and decided it was okay to invest their money on 50 research studies and only obtain five or six positive results. On the delivery side, the same level of eagerness and readiness to invest resources hasn’t been observed.

The Seychelles and Mauritius are island nations that are currently the only two in the African region to have completely immunised more than 70% of their populace. Only 10% of nations still have mandatory immunisation rates. Low vaccination levels in Africa have sparked a discussion over whether the WHO’s target date, which appears unrealistic for many nations, is prudent as the deadline draws closer.

Recent research supervised by the African Centres for Disease Control and Prevention found that in Kenya, targeting vaccination programmes to immunise the elderly was more cost-effective than achieving 70% coverage throughout the general population. Prioritizing vaccination for the elderly, pregnant women, people with comorbidities, and healthcare workers offered the best value for money. Achieving high immunisation rates among some of the general public was especially costly in countries with young populations that had high exposure to COVID-19.

African nations may provide greater health benefits to their residents by funding other more cost-effective health programmes, according to the acting head of the Africa CDC Health Economics Programme, Dr. Justice Nonvignon. There is no question that COVID-19 vaccines are cost-effective in a number of situations, Nonvignon continued. However, it is equally obvious that they must exercise caution in how they allocate our resources as the pandemic develops.

According to Bradshaw, how the pandemic develops in the coming months will determine whether the 70% aim is still appropriate. The quest for an ambitious target like 70% would be tremendously important if new varieties emerge that are extremely deadly, transmissible, and represent a greater danger to humans who are unvaccinated, even if they are young and fit. Bradshaw adds that certain nations won’t ever reach that aim based on their existing rates. He claims that those nations’ resources would be better directed toward incorporating COVID-19 methods into crucial immunisation programmes and concentrating on the most vulnerable populations.

According to Bradshaw, one alternative that is available to everyone is to alter the 70% aim. He claims that after the June deadline has passed, regional organisations like the Africa CDC may collaborate with the WHO to generate new region-specific targets. Sampath cautions against estimating the success of many of the continent’s immunisation efforts by matching vaccination rates in Africa to the aim of 70% coverage. Sampath claims that 70% of African nations are not vaccinated. Only adults over the age of 18 are often eligible for vaccinations in most African nations, so the task doesn’t seem so daunting when you consider that these nations only need to immunise 40% to 50% of their population.

It can be inaccurate to evaluate vaccination rates without taking the eligible people in each nation into account. For instance, if a hypothetical nation had the United Kingdom’s population distribution but Kenya’s age-specific immunisation rate, its overall coverage level would be 30%, nearly double Kenya’s actual immunisation rate of 17%.

Only a handful of African nations disclose immunisation rates broken down by age category, with Kenya being one of them. The Kenyan vaccine distribution team can evaluate their success in relation to specific goals thanks to this demarcated data, which also enables them to spot coverage gaps and gauge the effectiveness of focused engagement tactics. Sampath and Bradshaw agreed that governments must first follow Kenya in creating data collection and reporting mechanisms that are adequate for the task if a more specialised measure for reporting immunisation coverage across Africa is to become a reality.

There needs to be a global repositioning, continues Sampath, with the realisation that Africa is not actually covered by the broad 70% brushstroke.