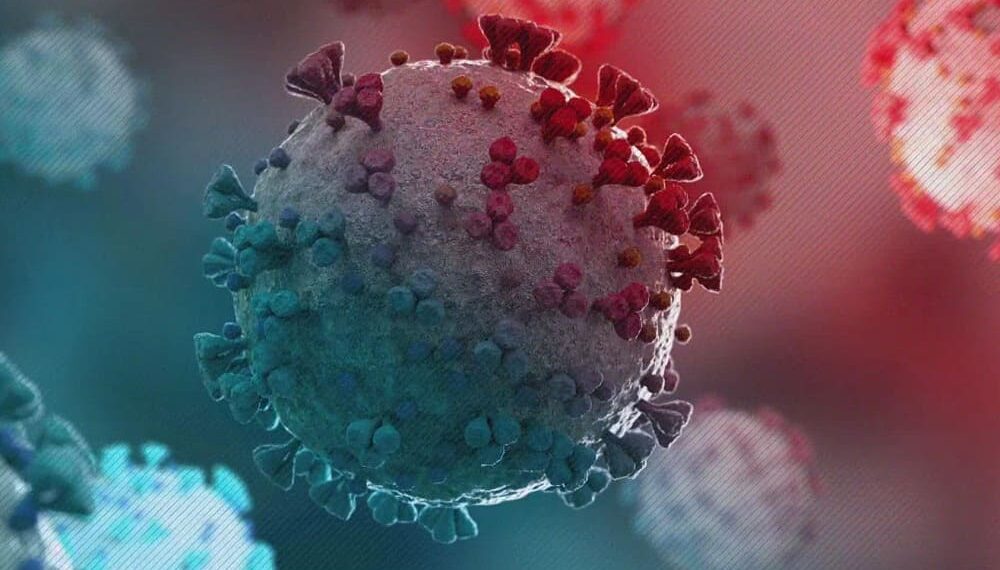

The data is undeniable: COVID-19 instances and hospitalizations are on the rise in the United States, despite patchy documentation. Most states are witnessing an upsurge, with Washington, Georgia, Mississippi, South Dakota, Nevada, Maine, Hawaii, and Montana seeing more than a 50% rise in cases compared to the prior week. Well over a quarter of New York’s population lives in a state with a “high” COVID-19 community level, implying that indoor masking is recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

According to data obtained by the US Department of Health and Human Services, daily average hospitalizations have increased by roughly 10% since last week. This time, the perpetrator seems to be BA.2.12.1, an offshoot of Omicron’s BA.2 subvariant that was first identified by New York state health officials in April. According to recent CDC estimates, BA.2.12.1, which is spreading approximately 25% faster than its parent virus, BA.2, accounts for at least 37% of all COVID-19 infections in the United States.

Last week, BA.2 was believed to be responsible for 62% of all COVID-19 cases, down from 70% the week before. BA.2.12.1 isn’t the only Omicron branch being studied by experts.

After weeks of dips, COVID-19 cases in South Africa have risen dramatically in the last two weeks. Scientists have witnessed two relatively novel subvariants, BA.4 and BA.5, control transmission in that country. As per South Africa’s National Institute of Communicable Diseases, it accounted for nearly 60% of all new COVID-19 cases by the end of April. These new Omicron subvariants are gaining traction all around the world. According to one of the portals, which is managed by a consortium of academic research institutes and funded by the National Institutes of Health, BA.4 patterns have been detected in 15 countries and 10 US states, while BA.5 sequences have been detected in 13 countries plus 5 US states.

BA.4 and BA.5 have quite a significant edge over BA.2, just like BA.2.12.1. A recent preprint report stated before peer review reveals why BA.4 and BA.5 are gaining momentum: They are immune to antibodies produced by past infections with the first Omicron virus, BA.1, the variation responsible for the massive wave of infections that hit numerous nations in December and January. They can also get through antibodies in people who have been vaccinated and have had breakthrough BA.1 infestations, though to a smaller extent than in people who have just been exposed.

In a laboratory, South African scientists evaluated the ability of antibodies in the blood to deactivate the BA.4 and BA.5 viruses. Non- vaccinated individuals who had recently suffered from a BA.1 infection observed a seven-fold reduction in their antibodies’ ability to neutralise BA.4 and BA.5 viruses. The decreases were smaller, almost three times lower, in people who had been immunised but recently had a breakthrough illness caused by BA.1.

By way of reference, the World Health Organization considers an eight-fold decline in neutralisation to be the point at which seasonal influenza vaccines need to be updated. The findings lead the researchers to conclude that BA.4 and BA.5 have the potential to result in a new virus surge, emphasising the importance of COVID-19 vaccines and booster shots in preventing the next outbreak.

So, first and foremost, Omicron isn’t a wonderful vaccine in and of itself. The study was directed by a virologist named Alex Sigal at the Africa Health Research Institute. Just because one has been infected doesn’t mean they will be immune to whatever is happening next.They’ve been first-rate all the way through the pandemic, said Dr. Eric Topol, a cardiologist and the Scripps Research Translational Institute’s founder and director.

At location 452 in their genomes, the BA.4 and BA.5 viruses, as well as BA.2.12.1, have mutations. This area is responsible for a portion of the virus’s receptor binding domain, which is the section of the virus that connects to a door on the surface of the cells. This is where the Delta variant and a few others have picked up mutations. Researchers believe that the alterations help the virus attach more securely to human cells and hide from antibodies, which are frontline immune fighters that try to prevent the virus from infiltrating the cells.

Scientists have started working to learn more about BA.2.12.1, which has been found in 22 nations, with the majority of sequences coming from the US. Andy Pekosz, a virologist and professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at Johns Hopkins University, said he has been cultivating BA.2.12.1 copies in his laboratory and has recently sent specimens of the virus to other research teams for analysis. Scientists have only recently begun discussing trials to try to answer two critical issues, like how fast is it replicating itself and how well does it evade immunity?

Scientists believed coronaviruses hadn’t changed much until the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The virus will continue to evolve as long as it finds new hosts to infect. This virus evolved slowly at first, but once it started picking up beneficial modifications, they just kept coming, he said.